Navigating a “challenging and difficult” path towards democracy

Navigating a “challenging and difficult” path towards democracy

Uzbekistan set out on a certain political path - a challenging and difficult one - and needed guidance on how to navigate the journey successfully.

Back in 2022, I participated regularly in meetings and interactions with constitutional scholars and governance experts from countries all around the world, including EU nations like Italy and Ireland. What would a Professor from an ex-Soviet Republic in Central Asia stand to gain from such activities?

The answer is: Uzbekistan set out on a certain political path – a challenging and difficult one – and needed guidance on how to navigate the journey successfully.

Remember, our country only gained independence from Moscow in 1991, and had only one head of state for the next quarter century. That was an era of stability and peace, during which President Islam Karimov provided a foundation on which to build the country’s future.

When our he passed away in 2016, his successor, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, decided that we needed to do more on behalf of our people. Uzbekistan, being the most populous nation in Central Asia, had a young and dynamic work force that counted on the President to provide them the chance to prosper. So he took the bull by the horns and sought to move Uzbekistan firmly into the 21st century. Knowing that the country had enormous untapped economic potential, he postulated that fully capitalizing on the growth possibilities would require changes to our political culture.

Reforms, therefore, became the order of the day, and have remained so for the past 8 years. President Mirziyoyev’s effort reached a major milestone last year when the citizens of Uzbekistan overwhelmingly approved a constitutional referendum that dramatically changed the parameters by which our government operates. But this was no flight-by-night exercise; rather, it was the culmination of years of preparation and study to make sure that Uzbekistan could move forward with confidence.

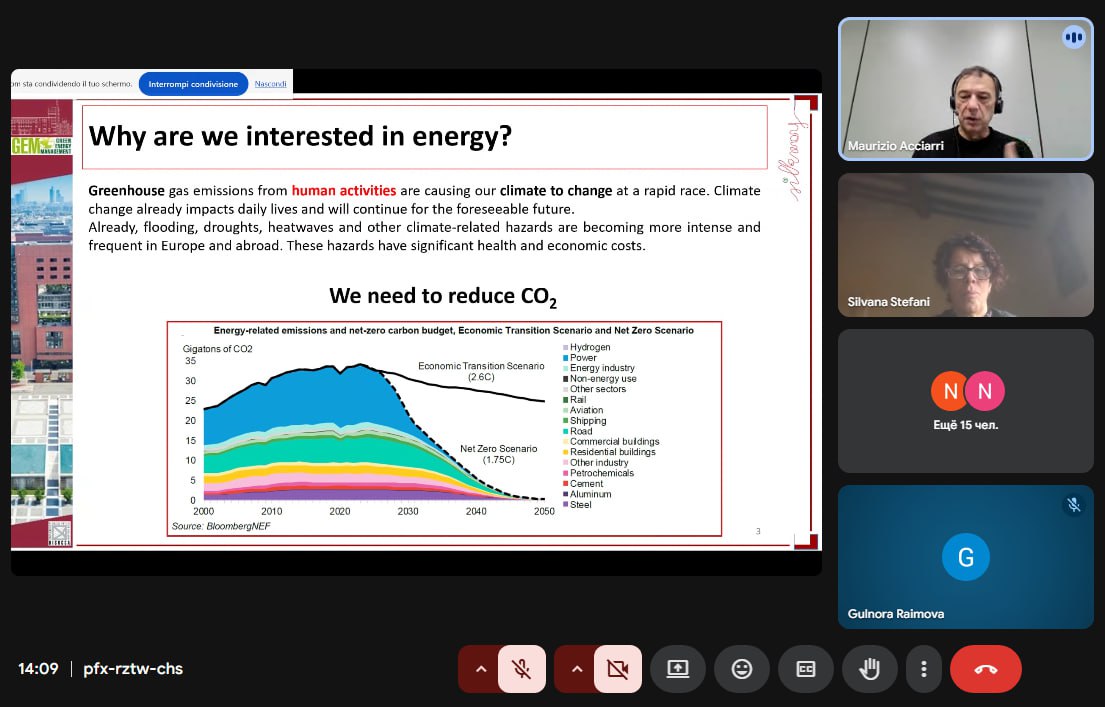

This is where my interactions with counterparts from around the world began. We embarked upon a comprehensive benchmark study of constitutional parameters from a myriad of countries in order to learn from their experiences – both positive and negative – with the goal of fashioning a new constitution that would give future generations of Uzbekistan’s citizens the best chance not only of long-lasting stability and peace, but of political liberty that would maximize economic competitiveness. The end result was a constitutional draft that drew upon best-in-class norms and clauses from dozens of nations from around the globe.

But the quest for reform did not stop there: the constitutional drafting committee also embarked upon a nationwide listening tour to solicit input from the citizens directly. Thousands of popular initiatives made it to the final draft submitted to referendum. Ultimately, that draft had changed from Uzbekistan’s original 1992 constitution by 65% percent.

The new constitution made advances in many areas, from environment to labor to minority rights to women’s rights and more. But in my view, the most significant changes concerned the country’s lawmaking process: what power would parliament ultimately have? What checks and balances would the new constitution impose? This may seem a trivial question when viewed with western eyes, but for a region with a historic tendency toward authoritarian rule, it cannot be understated.

For the first time, the presidency would cede powers to Uzbekistan’s parliament, called the Oliy Majlis, including appointing officials, such as members of the Supreme Judicial Council. The Senate shrinks from be 100 to 65 members and gains more control over law enforcement and special services agencies. The Legislative chamber will have more say in the formation of governments and in budgetary matters. For the first time both chambers will have the right of dissolution by a two-thirds majority.

And that brings us to today. Two months from now, voters will head to the polls to elect a new parliament for the first time since the new constitution was approved. The election itself changes from an exclusively “first past the post” method to a majority-proportional (mixed) system similar to that of Germany. Seventy-five of the 150 deputies of the Legislative Chamber will be elected from single-member constituencies under the “first past the post” system, while the remaining 75 will be chosen through proportional representation.

I am under no illusions about how the most cynical observers will choose to see this entire process. They disparage our reforms as insignificant, they critique us for a purported lack of political competition, they accuse us of “window dressing” an old regime, and they ridicule the credibility of our elections. With all due respect, these negative sentiments tend to roll off the tongues of those who, by accident of birth, inherited a robust and mature political system. I am aware of how easy it must be to sit in judgement of others at an earlier point in the trajectory of political modernity. Perhaps future generations of Uzbekistan’s citizens will reach the same point and will not appreciate the struggles that we face today to achieve a more advanced democracy on their behalf. It’s hard work, but hard work that we gladly accept to undertake today for the sake of their well-being tomorrow.

So let the cynics say what they will. Uzbekistan is committed to political reform, to multiparty parliamentary democracy, and to free and fair elections. To aspire to anything less would be to dash the best hopes of our people.

Gulnoza Ismailova,

Vice-Rector of UWED,

Doctor of Law, Professor